Because my work schedule is more restrictive than Richard’s, he comes over to eat lunch during my break. Most every day he is prompt and attentive to the time.

Sometimes, he’s with a patient and can’t come. Sometimes, he just forgets.

I usually try to page him if he isn’t on time to remind him.

On Thursday, he didn’t show up. I paged him. Nothing.

So, I went on with my meal and day and expected to see him later that afternoon.

When I got off work, I went back to our room to change for a run. The room was empty of Richard and some of his things were missing; backpack, Big Red parka, mountaineering boots.

Strange, I thought. After changing, I went over to the clinic to try to find him. His office was empty and strangely, no one else but Laura, the janitor, was around.

I eventually found Torri, the physician’s assistant. She told me that Richard made it onto a boondoggle trip for the day and he would be back sometime this afternoon.

“Oh, really,” I said. “Well, then I will stop worrying and start being jealous.”

A boondoggle is McMurdo-speak for an off-base trip with another group. It usually involves delivering or retrieving gear used by science groups, or helping them in some other way with their projects. Sometimes people dig holes in the snow or load and unload planes. Regardless, they are highly valued opportunities to experience a part of Antarctica that you certainly won’t get at McMurdo.

Here is Richard’s story of his boondoggle day:

“Saw three patients in the clinic, then got a call about a working boondoggle, and if anyone from medical would like to go… so I said yes, me.

By the time I sent a couple of other emails, I only had 20 minutes to put my contacts in, change and pack for the trip.

I got to the meeting spot and thought I had missed the shuttle since my watch said 10:02 a.m. and I was told to meet at 10.

I went in to medical and called fixed wing to tell them, then got two calls that I had not missed the shuttle, that it was right outside, but I had to go now, which I did.

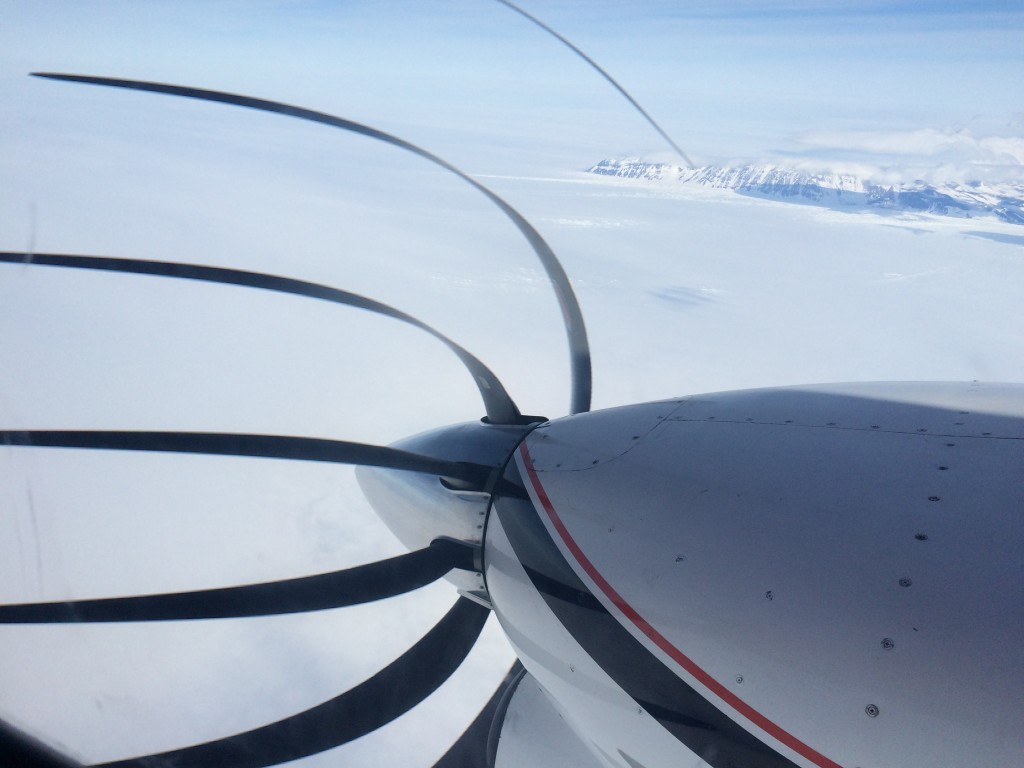

So, we got dropped off at Willie Airfield and got on a DC3/Basler made in 1941 using 1930’s technology. Granted it had had a few upgrades, but flying on a plane made before the end of WWII seems a little odd. The plane was pretty much empty on the way to the Crary Ice Rise camp (a small camp on the Ross Ice Shelf, about halfway to the South Pole, almost due south of here, 2 hours by flying) except for the 4 seats for us boondogglers, the two pilots and the “stewardess.”

The “Stewardess” was more of a tech position since he didn’t do much stewardessing and spent most of his time loading and unloading the aircraft, fueling the aircraft, tying stuff down, etc., but the pilots would give him a hard time by calling him the stewardess.

After two hours of flying along the transantarctic mountains, we landed in a field camp in fairly deep snow, making good use of the skis. The landing was much smoother than I thought it would be… I guess I thought the snow would be more ridged and hardpacked.

After going up and down the runway a couple of times to pack it down for the takeoff, we parked near the remains of the camp to be extracted from the snow and loaded it up.

There were about a dozen empty 55-gallon fuel barrels on a large pallet, four sleds, two snowmobiles, some shovels and bamboo and wood scraps.

One of the pilots started up a snowmobile and drove it around. He then used it to pull the sleds out as we dug them out, one by one. It was interesting to watch him then drive the snowmobile up a ramp, into the plane, then up the plane (since the front of the DC3 is higher than the rear) to the front where it was then strapped down.

Then the rest of the stuff (sleds, bamboo, the other snowmobile, empty fuel drums) was loaded up. We attempted to load the oversize military pallet that the fuel barrels were on, but after using a shovel and a cargo strap to measure it, we just couldn’t see how to make it fit in the DC3 (it had come out on a larger LC-130).

So we dug a trench parallel to the predominant winds and put the big pallet (resembles a giant version of one of those insulated cookie sheets) sticking up in a verticle fashion. Then we got back on the plane and flew back to Willy field.

We saw two more ships out in the ice breaker path leading to McMurdo as we were about to land and I assumed that the second was the tanker, bringing all the fuel that the base will use for the next year, but later found out it was a cruise ship anchored to the ice edge (partly because the icebreaker was blocking the path to get to McMurdo) and that it was using unmanned aerial video (drones)… which is why the DC3 pilot didn’t fly us over the ice edge to look for whales and penguins. He couldn’t fly near the drones and risk it flying into one of the engines. I want to see penguins!

We got back to McMurdo just in time to eat dinner, then Stephanie and I went to the science lecture about rapid access ice drilling (or RAID).”